There are numerous books and articles written on the subject. Inevitably, mainstream books present the popular Western narrative. In many cases, the so-called facts are just regurgitated propaganda material without any basis in fact.

Halide Edib, a Turkish intellectual, in her series of lectures delivered in the Jamia Millia Islami in Delhi in January-February 1934, which have been published in a book East Faces West, among other things, explains the decline of the Ottomans in philosophical terms and in the light of historical facts, as well as her own inferences from Ottoman lore. Halide was a contemporary of Mustafa Kemal Pasha. She begins her analysis of the decline of the Ottomans with the airs of a philosopher:

“There are two happenings in human life the exact time of which we can never tell. One concerns the individual, and that is the moment he falls asleep….The second concerns a nation. It is the moment of decline. No one can tell the exact date of it; everyone is conscious of it when it is in full swing.”

Edib, too, offers a positive aspect to the decline, in as much as Qurashi did when analysing decline of Muslim political power in India[1]. Halide Edib writes:

“No matter how agreeable the day’s work is, a man must sleep of his fatigue, rest and recuperate in order to begin a new day….Decline is the recuperation time, the rest-cure of nations. What a day is to the individual, a long historic period is to the nation…”

Like for other nations, it is difficult to assign a date when the decline started in the Ottoman Empire. Some historians put the date as 1774 when the Ottoman armies who faced a humiliating defeat in the harbour of Cesme on the Aegean Sea, were forced to sign the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774), concluding the war. (Maksudoglu, 1999, p. 195), (Edib, 2009, p. 54.)

The Ottomans in Good Times

To fully understand their decline and what they lost because of it, it is important to know of the grandeur and the might of the Ottomans in their hey days.

Edib (2009) articulated this aspect of the Ottomans crisply in one of her lectures delivered at Jamia Millia Islamia, Delhi, in January-February 1934.

“The Ottoman dynasty produced a record number of geniuses. They were trained for the army and the civil service and carefully educated. Their active service as governors or soldiers gave them first-hand knowledge and experience of the people over whom they were destined to rule. If a Sultan happened to be a genius, his training made him a world figure, if he were an ordinary man his training and experience made him work in harmony with the system without pulling it to pieces.”

(Edib, 2009, p. 61.)

Historians are unanimous that the zenith of Ottoman power was the time of Soleyman the Magnificent. He ruled over three continents; and in Europe his suzerainty extended to the walls of Vienna. “Great powers sought his allegiance, and his forces could beat the combined forces of the Western world on land and sea” (Edib, 2009). Mehmet Maksudoglu titles his chapter introducing Suleiman the Magnificent ‘The Superpower of the World” (Maksudoglu, 1999). He lists the numerous battles which were won by Suleiman and the new territories that were opened up for Islam during his reign, starting with Belgrade in 1521. Next to open up was the island of Rhodes on the Istanbul-Egyptian route.

Edib’s ‘Roxalene Decline Theory’

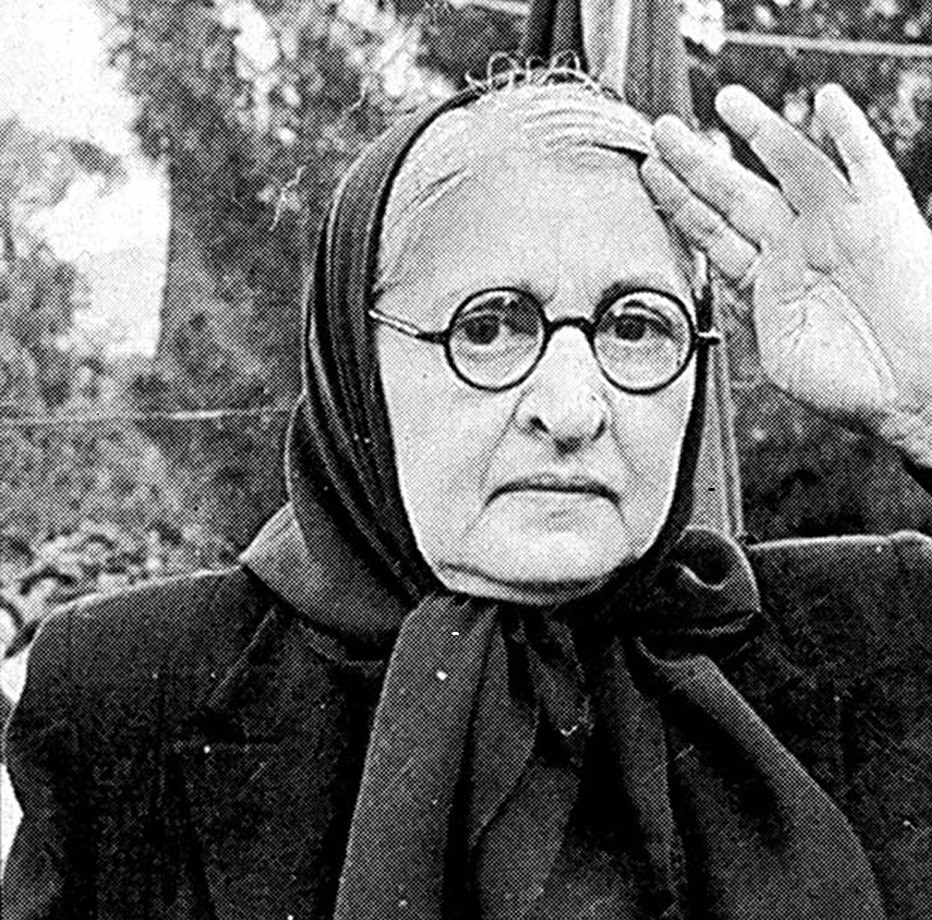

Edib’s take on the causes for the decline are somewhat novel. She blames Solaiman’s wife Hurrem Sultan for precipitating the downfall. She says, “But over Soleyman ruled his wife, Hurrem Sultan known as Roxalane to the Western world because of her Russian origin. This little woman with red hair and a turned-up nose was not much to look at, judging from her pictures, possessed a temperament and a capacity for intrigue which could beat all the Medici ladies put together” (Edib, 2009, p.61).

She lists numerous heinous crimes carried out by Hurrem, but the one single thing that, in Edib’s opinion, ‘dealt the fatal blow’ to the dynasty was the ‘Caged’ system that she persuaded Sulaiman to enforce for the princes, which meant, “The experimental and bodily part of the prince’s training was abandoned, though he was still taught the classics and given some education, and he was obliged to spend his life in the harem to the moment he could ascend the throne. The consequence was a series of hot-house princes, soft and ignorant of the conditions of their empire” (Edib, 2009, pp.61-62).

Ishtiaque Husain Qureshi’s own analysis of the decline of Muslim political power in India mentions almost identical factors:

“The community which had bred soldiers now bred dandies; gone were the days when princes had delighted in giving battle to wild tigers and enraged elephants;… it was not only an empire that fell; It was a community that fell from its moral pedestal and brought down with it all that had made it great and powerful”.

The Muslim Community of the Indo-Pakistan Subcontinent (610-1947), p.194.

Edib continues her analysis of the decline of the Ottomans in these words:

“The seventeenth century is a long record of evil Sultans. When they were not soft they were intolerable Tyrants, when they were the Harem brand they were vicious and incredibly corrupt. Favourite ladies began to sell every important post in the Empire. ‘the fish rots from the head’, we say. The civil service took its cue from the Sultan and bribery became quite a habit in the disposal of important offices. Merit, which had been the sole measure of promotion, became a vain word. Thus the Ottoman sultans, who had been more like the virile type of early Roman emperors, became like the Byzantine rulers. The Ottoman palace of these days was very much like the Byzantine palace […]

(Edib, 2009, pp.61-62).

Edib examines each organ of Ottoman society and how the decadence in these institutions led to the overall weakness of the Ottomans.

This notwithstanding, it is to the credit of the Ottomans that while ‘the Mughal Empire disappeared; Muslim successor states either disappeared or lost all autonomy. The Ottoman Empire, by contrast, continued and was still symbolically compelling even when it was weakened” (Barbara Metcalf, Islamic Revival in British India, p.7).

Army

Edib singles out the decline in the army, which was the backbone of the state system, as being most fatal. According to her, the Reform Bill of Cochi Bay, presented to Sultan Murad in the seventeenth century contains the principle change which caused the decline.(Edib, 2009, p. 62)

Judicial and Religious Class

Edib then states that the judicial and the religious class which was independent of the legislature and the executive but a very important part of the machinery, also began to decline. Edib concedes that “its position as protector of the religious liberties of the non-Muslims it retained, indeed, down to the time of Abdulhameed II and not only in the time of Selim the Grim, but in the seventeenth century as well, it had to protect the Christians”. She regrets that despite being an independent moral power, which could curb the excesses of the Sultans and, by their Fetva,, could depose the Sultan, they were forced to cooperate with the army and meddle with politics all the time. Thus, Edib’s opinion, they were no longer a neutral judicial and religious body, and religion became a pawn in the political game”. (Edib, 2009, p. 64.)

Comparing the position of the Ottoman ‘ulama with the functionaries of the Church in Western Europe who had reconciled to modern science and allowed freedom of thought, she indicts the Ottoman ‘ulama of complacency and stagnation. She continues her scathing attack on the ‘ulama in these words, “Further, during the age of decline, they were so occupied with politics that it seemed far the easier to stick to Aristotle, to reasoning as the basis of knowledge, rather than venture on observation and analysis. Therefore, the Medresses remained up to the end of the last century what they were in the thirteenth century. The ‘Vakf’ or Mosque schools, which were the sole organisation for primary education, remained similarly unchanged…” .(Edib, 2009, p. 66)

She blames what she feels as the obscurantism of the ‘ulama as responsible for making the Muslim youth who, after 1860, attended the state schools where science was being taught, conceive the idea that Islamic Teachings was an obstacle to progress and truth. In Edib’s opinion, this led to their “anti-clericism which became as irascible and as fanatical as a new religion”. .(Edib, 2009, p. 66.)

Edib adds, “Educationally, the non-Muslim nations fared better than Muslims. I cannot say that Christian nations during the age of our decline produced anything great, but on the whole they were aware of the changes in the outside world, and from a material point of view they profited by their knowledge. They were also in a position to profit, for the Muslim peoples, especially the Turks, were almost always on the battlefield”. (Edib, 2009, pp. 67-68.)

A contemporary historian, widely recognized as an authority on Ottoman history, holds a rather contrary opinion of the ‘ulama of the Ottoman period and says that the ‘ulama were actively involved in framing the syllabi for the religious schools as well as the secular schools. His views can be heard in this podcast https://www.thinkingmuslim.com/podcast/ep55-yaqoob-ahmed-ottomans. Yakoob Ahmed’s PhD thesis was on the role of the ‘ulama during the Ottoman rule, especially during the Hamidiian period. His research brings out the positive role the ‘ulama played in modernizing Turkish education. His lectures, organized by the Yunus Emre Institute, are available on YouTube (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NamIt9tpNyU&t=674s)

Economic Decline

Edib’s analysis of the difference between the economic position of the Muslim and Christian nations as well as the general economic decline of the Muslims leads her to say that this is one of the important features of this period. She claims that the question has unfortunately not been sufficiently studied with an unbiased mind. (Edib, 2009, p. 68.)

The Great Eastern Crisis (1875)

One of the major causes for Ottoman decline, as agreed upon by most historians, was the uprisings by the orthodox Christians in the Balkan states. Edib’s perspicuous insights on the subject of why the European powers were inciting the Christian population in Ottoman lands to rise in revolt, and why they were aligning with each other against the Ottomans, is worth pondering over.

Edib contends that, “The Ottomans had really frightened the Powers in the early period of their history. They were aggressive and for centuries victorious in Europe. The Crusades had failed to stem their expansion. Then the European Powers had begun to solicit Ottoman alliance in their own wars. But when the empire showed signs of weakness, it became an appetising piece, and each Power dreamed of carving out the best slice for itself. The Ottoman Empire was called the ‘Sick Man’ whose possession and property had to be divided among the Western Powers. They began to bargain and bicker over their prospective shares among themselves. Their rivalries, alliances, a whole series of actions and policies which constitute one of the most exciting but ugly chapters of modern history, are collectively called the ‘Eastern Question’. (Edib, 2009, p. 70.).

To speed up the decline of the Ottomans, the Powers incited the non-Muslim groups in the Balkans. Their two trump cards were religion and nationalism, she asserts.

It started as skirmishes by the so-called Balkan Confederates, comprising the Christian population of the Ottoman territories. These skirmishes were instigated and prodded on by Russia, who had always preyed on a weak Ottoman dispensation. The clashes resulted in the first of the many ethnic-cleaning campaigns against the Muslim minorities in the Balkan region, culminating in the horrific atrocities by the Serbs in Bosnia-Hercegovina in 1992—the biggest planned massacre of a population after WWII. (Bosnian Genocide, 2009, https://www.history.com/topics/1990s/bosnian-genocide)

[1] “Such occasions do sometimes produce analytical thinkers who try to diagnose the disease which overtakes a people. The plight of this community produced Shah Wali-u’llah”, Qureshi, Ishtiaq Hussain, The Muslim Community of the Indo-Pakistan Subcontinent (610-1947), Renaissance Publishing House, Delhi, 1985, p.198

Leave A Comment