Role of Kheiri Brothers, Prof. Danyal Bediz and Dr. Daud Rahbar

Abridged and condensed from the article by M. lkram Chaghatai titled, Dr. Daud Rahbar, First Pakistani Urdu Teacher in Turkey, published in the journal, Tehseel of the Islamic Research Academy, Karachi, Vol: 1, No: 2, Jan-Jun. 2018

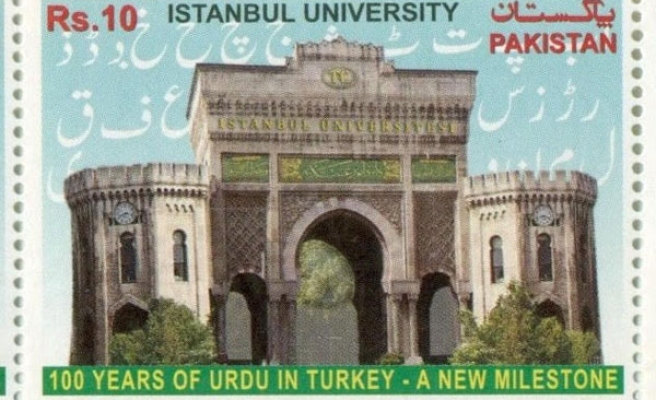

Turkey is, perhaps, the first country, outside the Indian sub-continent, that established a formal set up for teaching Urdu language over a hundred years ago— in 1915. Credit for this must go to two Kheiri Brothers –Abdul Jabbar Kheiri (elder, 1880-1958) and Abdus Sattar Kheiri (younger, d. 1945). These brothers belonged to an esteemed family of distinguished litterateurs and religious scholars of Delhi.

In 1904, the brothers left India for Egypt where they completed the religious education with distinction. They obtained M.A. degrees in Science and History respectively from the Syrian Protestant College. The beginning of the First World War (1914-1918) interrupted their educational plans. During the War, both took active part as members of Young Turks’ Committee of Union and Progress (CUP). Through Urdu and English journals entitled Akhuwwat and Brotherhood, both published from Istanbul, they launched a propaganda war against their opponents. This apart, they made arrangements for the teaching of Urdu language in Istanbul, aimed at strengthening the centuries-old political, literary and cultural relations between India and Turkey (Chaghatai, 2018).

For unknown reasons the Kheiri Brothers had to leave Turkey, and moved to Berlin (1918). Here, their persistent efforts for the propagation of Islam were rewarded and many learned personalities of the West embraced Islam including Leopold Weiss alias Muhammad Asad (1900-1992)[i].

More than three decades had passed since the departure of the Khairi brothers from Turkey, and the teaching of Urdu was suspened. But, after many time-consuming procedural formalities, a new Chair of Urdu and Pakistani Studies was established at Ankara University.

This time, the initiative came from Prof. Danyal Bediz, Professor of Economic Geography at Ankara University. He was brought up in Istanbul during the Balkan Wars. In those days, 1912-1913, the Muslims of India had organized three medical missions to support the work of the Turkish Red Crescent Society. The most popular and well-organized of these three missions was the Indian Medical Mission led by Dr. Mukhtar Ahmad Ansari—a distinguished physician of India who started his career in England’s best hospitals, but, later, after his return from Ottoman Turkey, immersed himself in the freedom struggle of his homeland, India.

This Medical Mission pitched its tents outside Istanbul. Many citizens of the city were touched by this gesture of fellow-Muslims from India. The father of young Danyal Bediz invited Dr. Ansari to his residence for a meal. The children were presented to the guest and were photographed with him. The memories of this visit remained alive in the mind of Danyal Bediz.

Around 1950, Prof Bediz became a good friend of the then Pakistani ambassador to Turkey, Mian Bashir Ahmad. The Ambassador was a poet of Urdu and had edited the literary journal Humayun for many years. With his support, Prof Danyal Bediz delivered numerous lectures in Turkey about the Muslims in Pakistan and India. He reminded his compatriots that the history of India was closely linked with the history of Turks. He talked about the Turk dynasties of India. He also made the event of the Indian Medical Mission to Ottoman Turkey better known to the Turkish public. His objective was to persuade his people to stop being cold to the Muslims of Pakistan and India, urging them to reciprocate the sincere contributions of the Indian Muslims. Ironically, Mian Bashir Ahmad had to leave Turkey since he was found to be “immoderately’ visiting mosques and holy shrines. During this period, Turkey had closed mosques and had imposed a ‘totalitarian secular order’[ii].

Incidentally, when Prof. Danyal Bediz proposed the setting up of an Urdu teaching center in Ankara University, the idea attracted the attention of the NATO countries, especially the US, who wanted secular Turkey to get closer to Islamic Pakistan, fearing Turkey’s extreme secularism may soon thrust them into the Communist camp.

Mian Bashir Ahmad was succeeded by Mian Aminuddin, who endeared himself to the Turks. Through his efforts, this chair was established by an Act of the Turkish Grand National Assembly.

The decision of establishing this Chair was conveyed to the Ambassador of Turkey in Pakistan who immediately contacted Dr. Maulavi ‘Abdul Haq (1870–1961), popularly known as Baba-i Urdu due to his life-long endevours at promoting Urdu language, to find a suitable candidate who could take up the responsibility of the Chair. Maulavi Abdul Haq proposed the name of Daud Rahbar, a young and promising scholar and son of his intimate friend, Dr. Sh. Muhammad Iqbal.

On Maulavi ‘Abdul Haq’s strong recommendation, Dr. Daud Rahbar was selected for this Chair. However, his final appointment took considerable time to materialize since the consultations between the governments of Turkey and Pakistan moved slowly.

From the summer of 1954 to the end of 1955, Daud Rahbar heard nothing from both ends. Eventually, Ankara University wanted him to join by 1st March 1956. But, just as he was about to set sail, he was asked to postpone his coming by six months due to procedural matters. He ultimately landed in Turkey in the Spring of 1956 with his wife and two daughters.

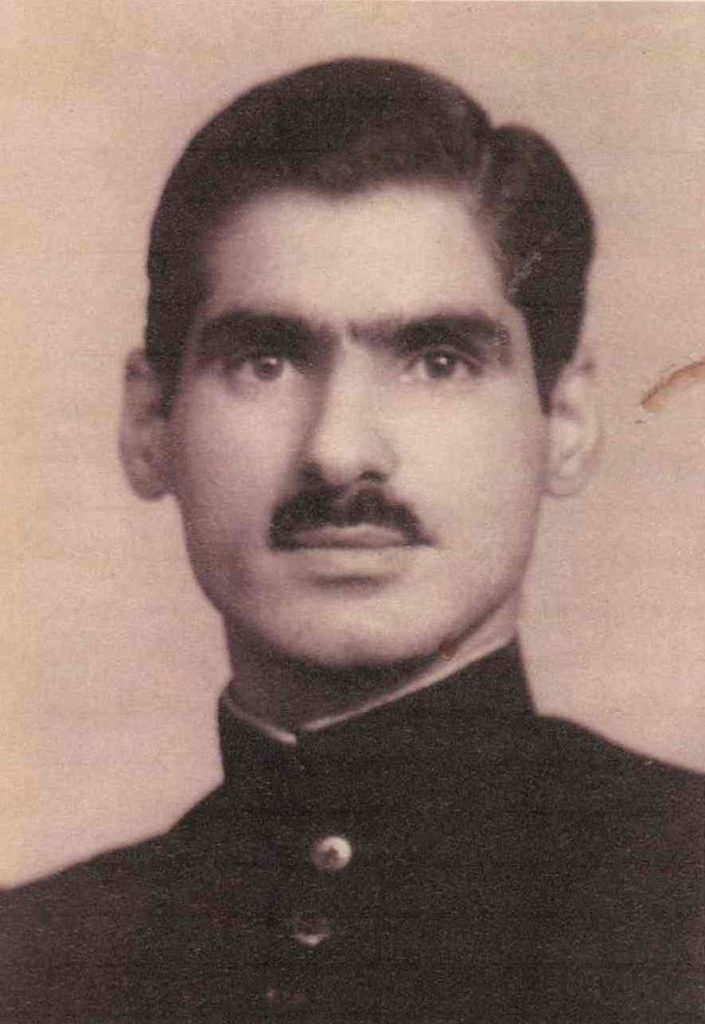

Daud Rahbar was the son of Sh. Muhammad Iqbal (1894-1948). Sh. Muhammad Iqbal was a student of the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College of Aligarh (1912), which later became the Aligarh Muslim University. Being a star student he won a state scholarship for research work in England. In Cambridge, he did his PhD under the guidance of E. G. Browne (d. 1926). He returned to India and in 1923 and became professor of Persian at the Punjab University, Lahore; a position he held until his death.

Daud Rahbar was born in Lahore in 1926. After completing his school, he joined Government College in 1941 and then the Oriental College of the Punjab University in 1945 where his father had taught. He passed M.A. in Arabic. After the creation of Pakistan, he went to Cambridge in April 1949 and served as a teacher in the University for five years. Later, he worked with Wilfred Cantwell Smith in the Institute of Islamic Studies, Canada, from 1954 until his departure to Turkey to take up the post of the chair of Urdu in Ankara University.

While in Ankara University, Daud Rahbar enrolled for a doctorate in “Persian Literature under the Seljuqs”. His interest in the Seljuqs was inherited. His father’s favourite field of studies was Seljuq history. Daud had made the acquaintance of two historians in Turkey, Ahmed Ate and Necati Lugal. They revealed that not only were they aware of his father’s works but had based their Turkish translations of two classics of Seljuq history on the works of his father.

On several occasions during his three years’ stay in Turkey, Daud Rahbar had to face the question: “Why do Muslims in Pakistan hold on to the Arabic or Persian script? Why don’t they adopt the Latin script for Urdu?” He would respond by saying that during the British rule, some influential linguists strongly recommended to switch to the Latin script but they failed because a majority of the writers and readers opposed this proposal and continued to use Naskh and Nasta’liq scripts.

The Turco-Pakistani Association of Ankara requested Daud Rahbar offer a course in the Urdu language for the benefit of the public in Ankara. He agreed to teach such a course without remuneration.

The course was advertised in the press as a course in “Ordu Dili”. Incidentally, the word Urdu or Ordu literary means army. When Daud Rahbar went to the first meeting of this class, he stood before fifteen officers of the Turkish army. They apparently thought that the course involved learning some sort of army language. Yet, most of them faithfully completed the three months’ course.

During his classes, Daud had to rely on an interpreter on many occasions. Finally, one day, he stood before the class and, in his faltering Turkish, he taught them for a full two hours. This performance was greatly appreciated by his students, who now began to call him fedakdr hocamcz (our dedicated teacher).

[i] Gunther Windhager: Leopold Weiss alias Muhammad Asad. Von Galizien nach Arabien 1900-1927. Vienna: Bohlau, 2000, 2nd ed., 2003, pp. 177-180, “Die Konversion in Berlin”; Florence Heymann: Un Juif pour !’Islam. Paris: Stock, 2005, pp. 186-201, “Au temps de la conversion”; M.Ikram Chaghatai: Muhammad Asad—An Austrian Jewish Converted Muslim. Lahore 2011, reprinted: 2015; Ibid.: Muhammad Asad: Europe’s Gift to Islam. 2 vols., Lahore 2006. Reprinted 2015.

[ii] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rx9bElkkEns in this video, Daud Rahbar, speaks about the ‘totalitarian secularism’ of Turkey during his tenure there as a chair of Urdu and Pakistan studies.

Wonderful